by Iraklis Symeonidis, COSIC, KU Leuven

and Gergely Biczók, CrySyS Lab, BME

Recent technological advancements have enabled the collection of large amounts of personal data at an ever-increasing rate. Data analytics companies such as Cambridge Analytica (CA) and Palantir can collect rich information about individuals’ everyday lives and habits from big data-silos, enabling profiling and micro-targeting of individuals such as in the case of political elections or predictive policing. As it has been reported at several major news outlets already in 2015, approximately 50 million Facebook (FB) profiles have been harvested by Aleksandr Kogan’s app, “thisisyourdigitallife”, through his company Global Science Research (GSR) in collaboration with CA. This data has been used to draw a detailed psychological profile for every person affected, which in turn enabled CA to target them with personalized political ads potentially affecting the outcome of the 2016 US presidential elections. Whether CA used similar techniques at the time of the Brexit vote, elections in Kenya and an undisclosed Eastern European country (and several other countries) is under investigation. Both Kogan and CA deny allegations and say they have complied regulations and acted in good faith.

This blog post does not take sides in this debate, rather, it provides technical insight into the data collection mechanism, namely collateral information collection, that has enabled harvesting the FB profiles of the friends of app users. In this context, the term collateral damage refers to the privacy loss these friends suffer. In a larger nexus, this issue is part of interdependent privacy when your privacy depends unavoidably on the actions of others (in this case, your friends).

Collateral information collection

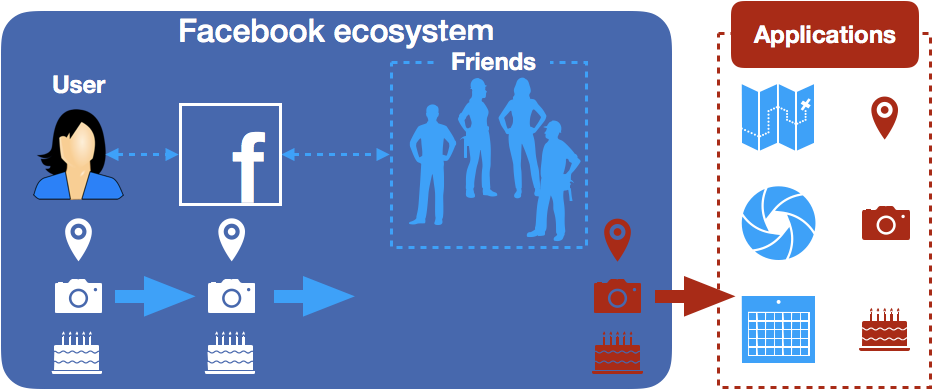

Facebook has morphed into an immense information repository, storing individuals’ personal information; logging interactions between users and their friends, groups, events and pages. It also offers third-party applications (apps) developed by third-party application providers (app providers). While installing an app on Facebook, it enables access to the profile information of a user. Accepting the permissions, the app collects personal and often sensitive information of the user, such as profile image, dating preferences, religious and political interests.

From a technical standpoint, Facebook provides an Application Programming Interface (API) and a set of permissions that allows third-party apps to gain access and transfer the information of users to app providers. Up until 2014 (2015 for already existing apps, Graph API v1.0) the profile information of a user could also be acquired when a friend of a user installed an app effectuating privacy interdependence on Facebook. Facebook claims that since 2015 (Graph API v2.0), this problem has been mitigated by changing the permission system, requiring mutual consent and mandating app reviews. A user who shared personal information with his/her friends on Facebook had no idea whether a friend had installed an app that also accessed the shared content. In short, when a friend of a user installed an app, the app could request and grant access to the profile information of a user such as the birthday, current location, and history. Such access took place outside the circle of trust, the user was not aware whether a friend had installed an app collecting his/her information; collateral information collection was enabled only based on the friend’s consent and happened without the consent of the user herself. By default, almost all profile information of a user could be accessed by their friends’ applications, unless they manually unchecked the relevant boxes in “Apps others use”. Note that, in some cases, one or more app providers may offer several applications and thus potentially construct a more complete personal profile via data fusion. Such fusion is straightforward to carry out, as all users are assigned a unique ID on Facebook that carries over to any app. This “feature” is still available and will not be affected by FB CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s recent privacy-enhancing announcements.

Collateral damage

We have been studying the interdependent privacy issues of third-party FB apps since 2012, showing the existence of the problem, investigating whether FB users cared about the issue and trying to quantify its likelihood and impact. Our main findings were the following:

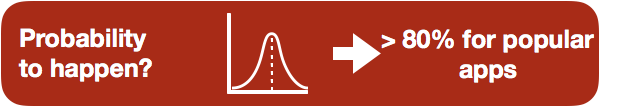

Is it likely that an installed application enables collateral information collection?

To answer this question, we computed the probability of the following event in the Facebook ecosystem: one of the friends of a user installs an application that requests friend permissions and enables collateral information collection. Taking into consideration the FB network topology and app adoption dynamics, we concluded that the likelihood of collateral information collection for a given user depends on the number of her friends and the popularity of the app under study. Assuming a single app with more than 5 million active users (such as TripAdvisor), there is an 80% probability for this risk to materialize for an average user.

How significant is the collateral information collection?

Utilizing real data from the Facebook third-party apps ecosystem (from the AppInspect study by Huber et al.), we computed the proportion of profile information collected by apps installed by the friends of a user.

We identified that almost half of the popular apps (more than 10,000 monthly active users) that enable the collateral information collection, collected the photos of the friends of a user, with location and work history being the second and third most popular attributes. 72% of these apps collected exactly one profile item in a collateral fashion, the remaining 28% somewhere between 2 and 11; this amounts to an average of 2 profile items collected per app. We also showed that some app providers do acquire more complete user profiles by offering multiple apps.

Is collateral information collection a risk for the protection of the personal data of Facebook users?

Through the prism of the new European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), we clarified who most likely the data controllers and data processors are. Second, we verified whether collateral information collection is an adequate practice from a data protection point of view. Finally, we identified who is accountable. We concluded that such collateral information collection is likely to result in a risk for the protection of the personal data of the Facebook users. The cause is the lack of notification (transparency as per Article 5 GDPR) and consent (consent as per Articles 6 and 7 GDPR), the non-existence of privacy by default in Facebook’s privacy settings, and the amplifying effect of data fusion and, potentially, profiling.

The collateral information collection goes far beyond the legitimate expectations of users and their friends. Consent can only be given by the person whose data is collected, not by the friend – the only exceptions are cases where the user cannot give consent (e.g. children under a certain age, in which case parents can give consent). One could claim that consent has implicitly been given since Facebook application settings allow users to control their settings; users can uncheck the appropriate privacy settings (i.e., “Apps Others Use” sub-menu). However, consent needs to be a “freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes […] by a statement or by a clear affirmative action” (art. 4 (11) GDPR), therefore unchecking a box will not be sufficient for consent. Adding to this, “Apps Other Use” has not really functioned since the deprecation of Graph API v1.0 in 2015: it has remained in the user interface as eye candy but has not resulted in more or less protected profile items.

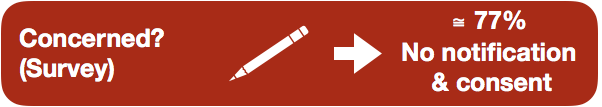

Are users concerned that apps installed by their friends can collect their profile data on Facebook?

We also investigated the opinion of Facebook users: are they concerned about collateral information collection? We designed a questionnaire and distributed it among 114 participants, to identify their concerns on collateral information collection, lack of transparency (notification) and not being asked for their approval (consent). We identified that the vast majority of our participants, i.e., 77%, is very concerned and would like proper notification and control mechanisms regarding collateral information collection. On top of that, their concern is bidirectional: they would like to both notify their friends and be notified by their friends when installing apps enabling collateral information collection. They would also like to restrict the apps accessing the profile data of both the user and their friends, when their friends enable collateral information collection and vice versa.

Outlook

Our academic study was based on real data on which permissions FB apps actually ask for and thus which personal profile items they can gather. We believe that our computations with regard to collateral damage showed that it is indeed an interesting and practical issue and a worthy research topic. Strengthening our case, we found that collateral information collection was problematic under the new European data protection legislation and that users were absolutely concerned by it. However, it was the detailed, multi-angle media coverage of the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica case that really put our numbers into context and increased interest in our research. Finally, it is important to note that Kogan’s “thisisyourdigitallife” is only one of many FB apps that have collected friends’ personal data. In fact, the interdependent privacy/collateral damage issue is not limited to the FB platform; it is fairly ubiquitous in our connected age: it is present on mobile platforms, in cloud apps and location-based services, and even personal genomics services.

A special thanks to Jessica Schroers (CiTiP, KU Leuven) for her expert opinion on legal implications.

References

This blog post is based on joint research between KU Leuven (COSIC and CiTiP), BME (CrySyS) and UAB (dEIC) universities.

This joint research resulted in a series of papers (in reverse chronological order):

- [1] Collateral Damage of Facebook Applications: a Comprehensive Study

- [2] Collateral Damage of Facebook Apps: Friends, Providers, and Privacy Interdependence

- [3] Collateral damage of Facebook Apps: an enhanced privacy scoring model

- [4] Interdependent Privacy: Let Me Share Your Data (this paper was published when authors were affiliated with NTNU)

We have also received extensive media coverage recently:

- [WIRED] The privacy setting that doesn’t do anything at all

- [NBC] Researchers say it was easy to take people’s data from Facebook

- [AOL] Researchers say it was easy to take people’s data from Facebook

- [France24] Cambridge Analytica : le scandale qui fait trembler l’empire Facebook

- [Medium] The Graph API: Key Points in the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica Debacle

- [Cadenaser] Los datos que obtuvieron los creadores de Cambridge Analytica sobre los usuarios

- [TheAtlantic] What Took Facebook So Long?

- [Nepszava] Zuckerberg bánja – Perek elé néz a Facebook-guru